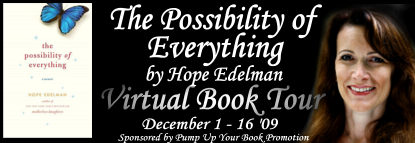

Join Hope Edelman, author of the book of the personal memoir, The Possibility of Everything (Ballantine Books), as she virtually tours the blogosphere in December on her first virtual book tour with Pump Up Your Book Promotion!

I will be reading this over this week - there's been a slight delay in my reviewing due to a surgery that came up with one week's notice. So watch for my review in the coming week - but for now enjoy some information about the author, the book and an excerpt. Also check out the other blogs participating in the tour.

Thanks to Pump Up Your Book Promotion for providing me with this book.

About Hope Edelman

Hope Edelman holds a bachelor’s degree in journalism from Northwestern University, and a master’s degree in English from the University of Iowa. She is the author of five nonfiction books: the international bestseller Motherless Daughters (1994), which was translated into seven languages; Letters from Motherless Daughters (1995), an edited collection of letters from readers; Mother of My Mother (1999), which looks at the depth and influence of the grandmother-granddaughter relationship; Motherless Mothers (2006), about the experience of being a mother when you don’t have one, from HarperCollins; and The Possibility of Everything (2009), her first book-length memoir, set in Topanga Canyon, California, and Belize.Hope has lectured widely on the long-term effects of early parent loss. She has appeared on national and local television throughout the U.S., including the Today show and Good Morning America, and has also appeared on TV and radio in Toronto; Vancouver; London; Sydney; Melbourne, Australia; and Auckland, Wellington, and Christchurch, New Zealand.

She began her journalism career with a part-time job at Outside magazine, and soon after interned for three months at the Salem Statesman-Journal in Salem, Oregon. Her first full-time editorial job was at Whittle Communications in Knoxville, Tennessee. From there, she went on to the University of Iowa, earning a master’s degree in creative nonfiction writing in 1992, one of the first of its kind.

Since then, her articles and essays have appeared in numerous publications, such as the New York Times, the Chicago Tribune, the San Francisco Chronicle, the Washington Post, the Dallas Morning News, Glamour, Child, Parenting, Seventeen, Real Simple, Self, The Iowa Review, and The Crab Orchard Review, and many anthologies, including The Bitch in the House, Toddler, Blindsided By a Diaper, and Behind the Bedroom Door.

She is the recipient of a New York Times Notable Book of the Year designation and a Pushcart Prize for creative nonfiction. Nearly every July you can find her at the Iowa Summer Writing Festival in Iowa City, and periodically at other conferences and festivals throughout the U.S.

Hope plays piano and guitar (sort of); cooks a mean French Toast; and has discovered an unexpected aptitude for sixth-grade math. She lives in Topanga, California, with her husband, their two daughters, a fat cat named Timmy (”No, Mom, tell them he’s buff!”) and their pet tarantula, Billy Bob.

You can visit her website at www.thepossibilityofeverything.com.

About The Possibility of Everything

From the bestselling author of Motherless Daughters, the real-life story of one woman’s search for a cure to her family’s escalating troubles, and the leap of faith that changed everything for her.In the autumn of 2000, Hope Edelman was a woman adrift, questioning her place in her marriage, her profession, and the larger world. Feeling vulnerable and isolated, she was primed for change. Into her stagnant routine dropped Dodo, her three-year-old daughter Maya’s curiously disruptive imaginary friend. Confused and worried about how to handle Maya and Dodo’s apparent hold on her, Edelman and her husband made the unlikely choice to bring her to Mayan healers in Belize, hoping that a shaman might help them banish Dodo-and, as they came to understand, all he represented-from their lives.

Examining how an otherwise mainstream mother and wife finds herself making this unorthodox choice, The Possibility of Everything chronicles the magical week in Central America that transformed Edelman from a person whose past had led her to believe only in the visible and the “proven” to someone open to the idea of larger, unseen forces. A deeply affecting and beautifully written memoir of a family’s emotional journey, it explores what Edelman and her husband went looking for in the jungle-and what they ultimately discovered-as parents, as spouses, and as ordinary people-about the things that possess and destroy, or that can heal us all.

Read the Excerpt!

A ragged dirt road twists through six miles of rain forest in

western Belize, linking the villages of Cristo Rey and San

Antonio. If you make this drive the day after a heavy December

rain, as my husband, Uzi, and I do, the road will still be gluey and

ripe. Its surface will be the color and consistency of mango pudding.

You might focus intensely on these two elements, mango and pudding,

to divert your attention from how the white van you’re riding in keeps

sashaying across the slippery road. And you might look down at the

three- year- old lying across your lap and think about how she is a child

who loves mangoes and loves pudding but that you have never thought

to put the two together for her before. You might look at her and think,

Mango pudding! Great idea! Let’s find a way to make some tonight! Or you

might think, If you’ll be okay, I’ll make you mango pudding every night for

the rest of your life. Or you might look down at her and just think, Please,

and leave it at that.Victor, our driver for this ride, maneuvers the eleven- seat passenger van with more skill and less caution than I could safely manage.“Hee- yah!” he calls out as he deftly steers us out of a skid. Every time

the van’s back end fishtails, I spring for the door handle. I don’t know

what I’m thinking: grabbing the door handle in an unlocked car is only

going to result in an open door on a muddy road, but when you’re ricocheting

around in the back of a van without seat belts, with a sick child

lying across your thighs, the impulse is to lunge for something solid. I tighten my right arm around my daughter Maya’s waist. Everything’s

fine, I tell myself. She’s going to be fine. I press my left hand against

the window and watch the landscape stream by between my fingertips.

The jungle grows flush against both sides of the road, tangled and pristine.

The bulldozers of American expatriates chewing up the Caribbean

coast haven’t found their way back here yet. Fat, squat cohune palms

burst up from ground level like Las Vegas fountains spraying out of the

forest floor. Thick, serpentine vines encircle tree trunks like lush maypole

ribbons. The biodiversity here is astounding. I never imagined

there could be so many different kinds of leaves in one place, or so

many shades of green.

The air outside is like nothing I’ve encountered before: energetic

and molecular and intense. A few hours ago, when we were sitting on

the front steps of our cabana at Victor’s resort, I took in deep gulps of

the jungle’s bright, wet promise, the loamy, rich animation of the dirt

marrying with chlorophyll to form air so dense it tempts you to take a

bite.

At lunch, we ate family style in an open- air dining hall lined with

rectangular wooden tables, under the thatched roof Victor and his sons

had woven from local palm fronds. While his wife and daughters

served heaping plates of rice and beans and bowls of fried plantains,

Victor meandered between the tables with a small pad of paper in one

hand and a bottle of orange Fanta dangling between the thumb and

forefinger of the other. As he approached each table he flipped a chair

around and sat on it backward, pulled a pen from behind his ear, and

scribbled down each family’s travel request for the day. A foursome of

fresh- scrubbed Brits— mother, father, daughter, son— wanted to go

canoeing on the Macal River. Two bearded men who looked too old to

still be backpackers wanted to see the nearby Maya ruins at Xunantunich.

A family from Montreal with two college- age daughters opted for

a few hours in the neighboring town of San Ignacio, a few miles downriver.

“Sure, sure,” Victor said to everyone, tossing back swigs from his

bottle. “We take you. No problem.” Victor quickly established himself

as part hotelier, part chauffeur, and part general contractor, a rainforest

Renaissance man in an olive green baseball cap. At our table, he

rested a hand on Uzi’s shoulder. We’d already put in our afternoon

request.

“Two o’clock,” Victor told us. “I’ll take you, or my son will.”

This drive to San Antonio rolls on. Our tires make loud sucking

noises as they peel away from the gummy earth. Off to our right, an

animal lets loose with what sounds like a familiar, plaintive howl. Maya

raises her head in recognition, pivots it around like a slow periscope,

then lets it drop back down against my thigh.

“You have coyotes here?” Uzi asks. He’s riding up front with Victor,

one hand braced against the glove compartment for support.

“What?” Victor maneuvers the van around a wide puddle.

“Coyotes,” Uzi says. “You know, like little wolves. We have them at

home.”

“Oh, yeah,” Victor says, swatting the air with his hand. “We got

anything you want here.”

Anything? Maya coughs her raspy cough against my leg, the sound

of gravel rattling between her ribs. I press my palm against her forehead.

I’m guessing 101, maybe 101.5, better than yesterday, but not by

much. I tuck a sprig of dark curls behind her ear.

Mi vida, I think. My life.

These words that come to me are not the words of my own country,

but those of a language I struggled to learn for years, a language

that both exhilarates me and breaks my heart. Mi vida. At home in Los

Angeles, it is the language of the hardworking and the oppressed, of the

woman who cleans my house with care once a week, of the man with

the white pickup truck who trims the palm trees that line our driveway,

of the childless nanny who loves my daughter with a selfless passion

while I spend hours in front of a computer screen rearranging words.

But here in Belize it is the language of conquerors, the language that

overtook the indigenous Maya and then, centuries later, turned around

and pushed out the imperial British masters. A language that says,

“Here. This. Mine.”

Victor sits calmly behind the van’s steering wheel. Perhaps he’s

made this drive for dozens of guests before. I imagine a steady parade

of Americans traipsing into the jungle in their Lakers caps and Teva

sandals, acting entitled to their cures. Yet surely, we must stand out

from the pack. There’s Uzi, who’s forty, though so boyish no one can

believe his age, with an Israeli accent so slight it barely dusts the surface

of his speech. He’s a quintessentially low- impact kind of guy, softspoken,

careful to tread lightly on the earth. Not like me, who can’t

help leaving footprints and food wrappers in my wake everywhere I go.

And there’s Maya, three feet tall with a mop of dark curls, carrying two

rubber baby dolls tucked under her right arm, refusing to eat anything

but cucumbers and water for the past three days because everything

else hurts going down.

And me? How might I look to someone I’ve just met? Probably like

a medium- aged American woman in striped cotton pants who’s equal

parts grateful and unsure about being here and who can’t stop hovering

over her three- year- old— checking, fixing, trying to coax forkfuls of

food past the child’s tightly shut lips. Or maybe I’m wrong. Maybe I

don’t make an impression at all. Maybe I’m just another tourist messing

up the bedsheets, acting as if I have a right to benefit from knowledge

that took Victor’s ancestors millennia to learn.

The low, brightly painted buildings of San Antonio Village appear

in the distance, like a handful of colorful marbles scattered across the

valley’s gentle bowl. The Maya Mountains rise blue- gray in the distance.

Maya coughs again.

“Ay, raina,” Victor sighs. He calls her “queen.”

Here in the land of the Maya, where body, mind, and spirit are

tightly intertwined, physical and spiritual illness are considered one

and the same. Physical symptoms, the Maya believe, erupt when the

life force that surrounds a person’s body, the ch’ulel, is damaged by

trauma or stress. Those who are sick in body are believed to first be sick

in spirit, and so Maya healers always treat both.

Uzi glances at me over his left shoulder, searching my face for a

sign. My gentle husband, always gauging my moods, always trying to

position himself on the safe side of conflict. Are you still okay with this?

his expression asks. I crimp the left side of my mouth and shrug my

shoulder slightly. I’m deliberately impossible to read.

Even now, eight years later, I cannot tell you if I traveled down

that road as a whole person, held intact by my own convictions, or if I

went there as a broken woman, mechanically following my husband’s

lead. I can tell you only what it is like to be riding in that van, on that

mango road, rolling past dense fields of brown and green. It is to be a

thirty- six- year- old woman, a mother and a wife, who is willing to do

anything—anything— to help her child.

Mi vida. I will tell you. This is how it feels. As if my life is lying

across my lap and I am bringing it into the jungle, to the man who

speaks with spirits, so it can be healed.

western Belize, linking the villages of Cristo Rey and San

Antonio. If you make this drive the day after a heavy December

rain, as my husband, Uzi, and I do, the road will still be gluey and

ripe. Its surface will be the color and consistency of mango pudding.

You might focus intensely on these two elements, mango and pudding,

to divert your attention from how the white van you’re riding in keeps

sashaying across the slippery road. And you might look down at the

three- year- old lying across your lap and think about how she is a child

who loves mangoes and loves pudding but that you have never thought

to put the two together for her before. You might look at her and think,

Mango pudding! Great idea! Let’s find a way to make some tonight! Or you

might think, If you’ll be okay, I’ll make you mango pudding every night for

the rest of your life. Or you might look down at her and just think, Please,

and leave it at that.Victor, our driver for this ride, maneuvers the eleven- seat passenger van with more skill and less caution than I could safely manage.“Hee- yah!” he calls out as he deftly steers us out of a skid. Every time

the van’s back end fishtails, I spring for the door handle. I don’t know

what I’m thinking: grabbing the door handle in an unlocked car is only

going to result in an open door on a muddy road, but when you’re ricocheting

around in the back of a van without seat belts, with a sick child

lying across your thighs, the impulse is to lunge for something solid. I tighten my right arm around my daughter Maya’s waist. Everything’s

fine, I tell myself. She’s going to be fine. I press my left hand against

the window and watch the landscape stream by between my fingertips.

The jungle grows flush against both sides of the road, tangled and pristine.

The bulldozers of American expatriates chewing up the Caribbean

coast haven’t found their way back here yet. Fat, squat cohune palms

burst up from ground level like Las Vegas fountains spraying out of the

forest floor. Thick, serpentine vines encircle tree trunks like lush maypole

ribbons. The biodiversity here is astounding. I never imagined

there could be so many different kinds of leaves in one place, or so

many shades of green.

The air outside is like nothing I’ve encountered before: energetic

and molecular and intense. A few hours ago, when we were sitting on

the front steps of our cabana at Victor’s resort, I took in deep gulps of

the jungle’s bright, wet promise, the loamy, rich animation of the dirt

marrying with chlorophyll to form air so dense it tempts you to take a

bite.

At lunch, we ate family style in an open- air dining hall lined with

rectangular wooden tables, under the thatched roof Victor and his sons

had woven from local palm fronds. While his wife and daughters

served heaping plates of rice and beans and bowls of fried plantains,

Victor meandered between the tables with a small pad of paper in one

hand and a bottle of orange Fanta dangling between the thumb and

forefinger of the other. As he approached each table he flipped a chair

around and sat on it backward, pulled a pen from behind his ear, and

scribbled down each family’s travel request for the day. A foursome of

fresh- scrubbed Brits— mother, father, daughter, son— wanted to go

canoeing on the Macal River. Two bearded men who looked too old to

still be backpackers wanted to see the nearby Maya ruins at Xunantunich.

A family from Montreal with two college- age daughters opted for

a few hours in the neighboring town of San Ignacio, a few miles downriver.

“Sure, sure,” Victor said to everyone, tossing back swigs from his

bottle. “We take you. No problem.” Victor quickly established himself

as part hotelier, part chauffeur, and part general contractor, a rainforest

Renaissance man in an olive green baseball cap. At our table, he

rested a hand on Uzi’s shoulder. We’d already put in our afternoon

request.

“Two o’clock,” Victor told us. “I’ll take you, or my son will.”

This drive to San Antonio rolls on. Our tires make loud sucking

noises as they peel away from the gummy earth. Off to our right, an

animal lets loose with what sounds like a familiar, plaintive howl. Maya

raises her head in recognition, pivots it around like a slow periscope,

then lets it drop back down against my thigh.

“You have coyotes here?” Uzi asks. He’s riding up front with Victor,

one hand braced against the glove compartment for support.

“What?” Victor maneuvers the van around a wide puddle.

“Coyotes,” Uzi says. “You know, like little wolves. We have them at

home.”

“Oh, yeah,” Victor says, swatting the air with his hand. “We got

anything you want here.”

Anything? Maya coughs her raspy cough against my leg, the sound

of gravel rattling between her ribs. I press my palm against her forehead.

I’m guessing 101, maybe 101.5, better than yesterday, but not by

much. I tuck a sprig of dark curls behind her ear.

Mi vida, I think. My life.

These words that come to me are not the words of my own country,

but those of a language I struggled to learn for years, a language

that both exhilarates me and breaks my heart. Mi vida. At home in Los

Angeles, it is the language of the hardworking and the oppressed, of the

woman who cleans my house with care once a week, of the man with

the white pickup truck who trims the palm trees that line our driveway,

of the childless nanny who loves my daughter with a selfless passion

while I spend hours in front of a computer screen rearranging words.

But here in Belize it is the language of conquerors, the language that

overtook the indigenous Maya and then, centuries later, turned around

and pushed out the imperial British masters. A language that says,

“Here. This. Mine.”

Victor sits calmly behind the van’s steering wheel. Perhaps he’s

made this drive for dozens of guests before. I imagine a steady parade

of Americans traipsing into the jungle in their Lakers caps and Teva

sandals, acting entitled to their cures. Yet surely, we must stand out

from the pack. There’s Uzi, who’s forty, though so boyish no one can

believe his age, with an Israeli accent so slight it barely dusts the surface

of his speech. He’s a quintessentially low- impact kind of guy, softspoken,

careful to tread lightly on the earth. Not like me, who can’t

help leaving footprints and food wrappers in my wake everywhere I go.

And there’s Maya, three feet tall with a mop of dark curls, carrying two

rubber baby dolls tucked under her right arm, refusing to eat anything

but cucumbers and water for the past three days because everything

else hurts going down.

And me? How might I look to someone I’ve just met? Probably like

a medium- aged American woman in striped cotton pants who’s equal

parts grateful and unsure about being here and who can’t stop hovering

over her three- year- old— checking, fixing, trying to coax forkfuls of

food past the child’s tightly shut lips. Or maybe I’m wrong. Maybe I

don’t make an impression at all. Maybe I’m just another tourist messing

up the bedsheets, acting as if I have a right to benefit from knowledge

that took Victor’s ancestors millennia to learn.

The low, brightly painted buildings of San Antonio Village appear

in the distance, like a handful of colorful marbles scattered across the

valley’s gentle bowl. The Maya Mountains rise blue- gray in the distance.

Maya coughs again.

“Ay, raina,” Victor sighs. He calls her “queen.”

Here in the land of the Maya, where body, mind, and spirit are

tightly intertwined, physical and spiritual illness are considered one

and the same. Physical symptoms, the Maya believe, erupt when the

life force that surrounds a person’s body, the ch’ulel, is damaged by

trauma or stress. Those who are sick in body are believed to first be sick

in spirit, and so Maya healers always treat both.

Uzi glances at me over his left shoulder, searching my face for a

sign. My gentle husband, always gauging my moods, always trying to

position himself on the safe side of conflict. Are you still okay with this?

his expression asks. I crimp the left side of my mouth and shrug my

shoulder slightly. I’m deliberately impossible to read.

Even now, eight years later, I cannot tell you if I traveled down

that road as a whole person, held intact by my own convictions, or if I

went there as a broken woman, mechanically following my husband’s

lead. I can tell you only what it is like to be riding in that van, on that

mango road, rolling past dense fields of brown and green. It is to be a

thirty- six- year- old woman, a mother and a wife, who is willing to do

anything—anything— to help her child.

Mi vida. I will tell you. This is how it feels. As if my life is lying

across my lap and I am bringing it into the jungle, to the man who

speaks with spirits, so it can be healed.

The Possibility of Everything Tour Schedule

Tuesday, Dec. 1Book spotlighted at Examiner

Wednesday, Dec. 2

Book reviewed at One Person’s Journey Through a World of Books

Thursday, Dec. 3

Book reviewed & giveaway at Luxury Reading

Friday, Dec. 4

Book reviewed at Readaholic

Guest blogging at As the Pages Turn

Monday, Dec. 7

Interviewed at Blogcritics

Book reviewed at My Reading Room

Tuesday, Dec. 8

Interviewed at The Hot Author Report

Book reviewed at The Life of an Inanimate Flying Object

Wednesday, Dec. 9

Reviewed at Review From Here

Reviewed at Rundpinne

Thursday, Dec. 10

Guest blogging at Blogging Authors

Guest blogging at Carol’s Notebook

Friday, Dec. 11

Book reviewed at A Sea of Books

Monday, Dec. 14

Interview l Chat l Book Giveaway at Pump Up Your Book!

Tuesday, Dec. 15

Book reviewed at Brizmus Blogs Books

Book reviewed and guest blogging at My Book Views

Wednesday, Dec. 16

Book reviewed at Buuklvr81